Cruising the Rivers

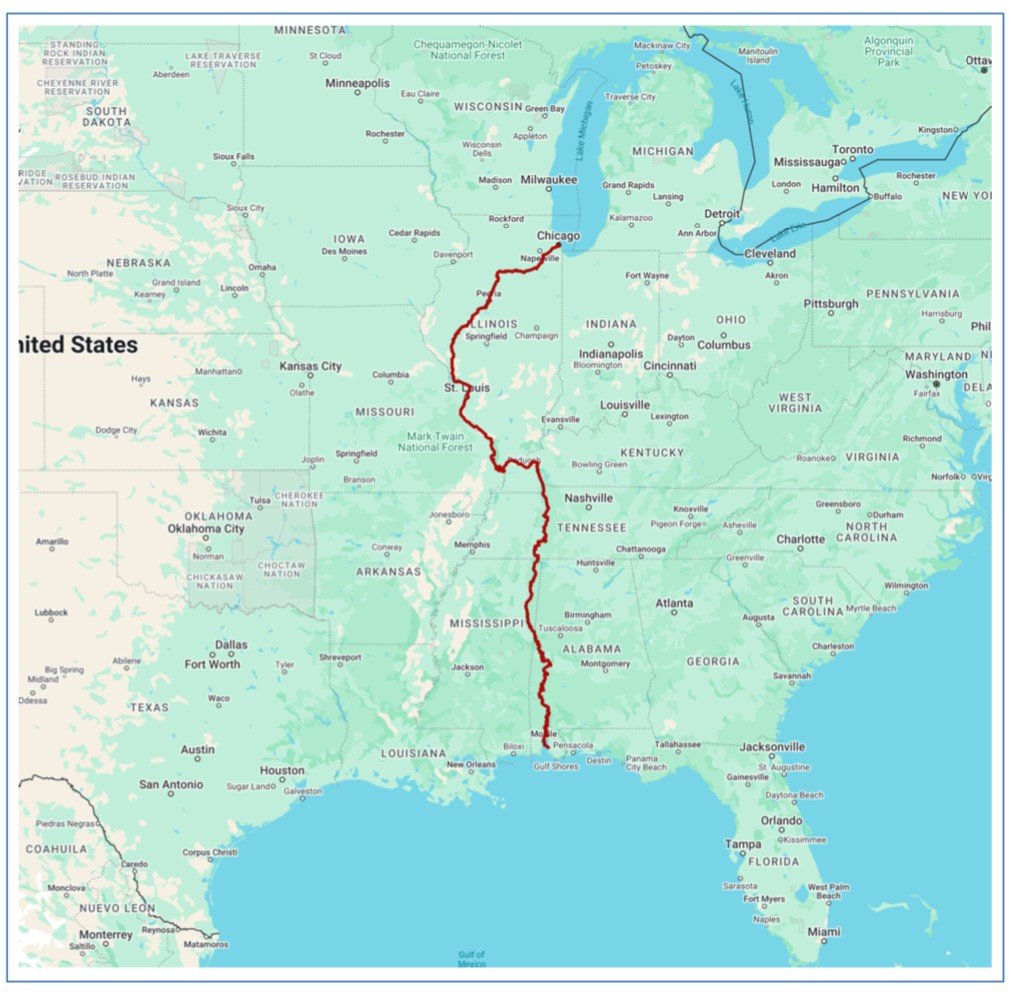

Cruising the river system from Chicago to Mobile was a lesson not only in geography but also one of history. We left the DuSable Harbor marina on the shore of Lake Michigan and started our month long, 1,534 nautical mile journey down the river system to the Gulf of Mexico (this was in before the change to the Gulf of America).

We were pleasantly surprised how much we enjoyed the diversity of the trip through six states; Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama. Cruising the rivers was an education in so many ways including navigating a total of 11 different rivers, many of which are connected to America’s development. When talking to people about our journey on the rivers many assume we traveled most of the way on the Mississippi River when in truth only 191 nm or only 13% of our journey was on the Mississippi.

Everyone that completes America’s Great Loop will pass through or around Chicago. The route they choose will depend largely on their boat’s air gap, or in other words what height bridge their boat can pass under.

The lowest fixed bridge on the loop is a railroad bridge on the Illinois River, just south of Chicago with a charted height of 19’ 7”. Loopers that choose to go through downtown Chicago must be able to comfortably pass under 17’, which is the charted height of the DuSable Bridge over Michigan Avenue. If this is not possible loopers must take the Cal-Sag channel, (shortened from Calumet-Saganashkee).

Our boat has an air gap of 14’ with the radar mast lowered so we chose to the downtown route. Our cruise through downtown Chicago was without question one of the highlights of our loop journey.

The transit between Lake Michigan and ultimately the Mississippi River was not possible before the creation of the Illinois Michigan Canal, which was open in 1848 and established Chicago as the transportation hub for the US, before the railroad era. The canal connected the Chicago River in the Bridgeport neighborhood of Chicago to the Illinois River at LaSalle Peru. The canal was partially replaced by the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal in 1900 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illinois_and_Michigan_Canal).

This newer canal was built to change the direction of the canal to flow from Lake Michigan to the Illinois and eventually Mississippi River for the purpose of carrying the city’s sewage away from the lake as this was the source of the city’s drinking water (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_River). Remnants of the old canal’s bulkheads and structures are evident as we cruised this section.

We transited 35 nm down the Chicago River, through downtown Chicago then the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal until Joliet, IL where we met up with the Des Plaines River for 12 nm to Wilmington, IL where we spent the evening. The next morning we turned on to the Illinois River and traveled 239 nm making stops in Ottawa and Peoria, IL. We ended up spending a few extra nights in Peoria waiting for remnants of a tropical storm to pass. We enjoyed our timing exploring Peoria with one of the highlights being the Caterpillar Visitor Center where we learned about giant dump trucks and earth moving equipment. We also learned that Peoria was the birthplace of singer Dan Fogelberg.

After Peoria we stopped in Grafton for a couple of nights. As we left Grafton we joined the Mississippi River and the amount of barge traffic increased considerably. This is understandable when we learned that each year approximately 500 million tons of goods are shipped via barges on the Mississippi River.

The barges transport primarily grain and around 90% of grain exported from the US from is transported via barges. We also saw a number of barges carrying sawdust for particle board and different sizes of stone and gravel.

Most of the barge “tows” we saw consisted of 12 to 15 barges, usually 3 wide and as many as 5 long. A tow is a group of barges lashed together by steel cables and pushed by a towboat.

Some amazing statistics,

A 15-barge tow on the is about 1,000 feet long and 105 feet wide

A 15-barge tow can carry about 22,500 tons of cargo

A 15-barge tow is equivalent to about 225 railroad cars or 870 tractor-trailer trucks

Barge transport is fuel efficient and environmentally advantageous.

In addition to the increased barge traffic we were back to having to manage and navigate through lift locks. The locks on the river system are much larger than those we passaged on the Erie Canal and Trent Severn Waterway as the ones on the river are designed to accommodate the large barge tows. In total we transited 22 locks on the rivers, the largest was at the start of this section of the journey being the Chicago Harbor lock which measured 80 feet wide and 600 feet long.

A couple of hours south of Grafton we passed in front of the iconic St. Louis Arch. Officially known as the Gateway Arch it was opened to the public in 1967, is 630 feet tall and is the world’s tallest arch and some say the tallest man-made monument in the Western Hemisphere.

The arch is commonly referred to as “The Gateway to the West” as it was built to recognize western expansion of the US. I link this to Lewis and Clark’s Corp of Discovery expedition that set out from St. Louis in 1804 to map out a route to the Pacific, hopefully mostly by water.

As we passed the Arch we also passed by the Tom Sawyer riverboat, which gives daily tours of this area of the river. Just south of St. Louis there is a sculpture of large legs in stripped socks. We love seeing these unique works of art as we cruise the different waterways.

Access to marinas and therefore fuel for recreational vessels is limited on the Mississippi River. Because of this everyone fuels up in Grafton before starting the trip south as the next fuel is over 200 nm away at Hoppie’s, which is little more than a barge tied along the shore of the Mississippi in Kimmswick, MO. After Hoppie’s our next stop was Kaskaskia lock wall and then a night at anchor off Bumgard Island. In total we travel 191 nm on the Mississippi River to Cairo, IL where we turn up-river onto the Ohio River.

We saw a net decrease in speed of about 6 knots from the Mississippi where we were traveling down-river with the current to the Ohio where we were traveling up-river against the current. A short way up the Ohio we stopped at Paducah, KY for a couple of nights. One of the highlights of the stop in Paducah was our visit to The National Quilt Museum.

From Paducah we traveled a short way before turning on to the Cumberland River at Smithland and then 33 nm where we meet up with the Tennessee River in Grand Rivers, KY. We spent five days at Green Turtle Bay Resort relaxing and exploring the area also known as “The Land Between the Lakes”, between Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake.

While researching and reading about the Tennessee River I learned about the Tennessee Valley Authority, TVA and its importance to the history not only to this region but to the entire country. In early 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act, which created the TVA as a federal corporation. The TVA was asked to tackle problems such as flooding, replanting forest and providing electricity to the region.

Due to the TVAs access to hydroelectric power and natural resources in the area it became a key force in the development of nuclear weapons during World War II as part of the Manhattan Project. The TVA hydroelectric dams supplied power to support the uranium enrichment in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

In addition to the work related to nuclear weapons TVA supplied large amounts of phosphorus and ammonia used in munitions, calcium carbide used to produced synthetic rubber and fertilizer to increase food production to support troops abroad, including allied forces.

In total the TVA has 49 dams in the Tennessee River system of which 29 generate electricity. In total TVA operates 70 electricity generating sites, including hydroelectric, nuclear, fossil fuel and solar making it the country’s largest public power provider with 34,000 megawatts of generating capacity. This equates to powering as many as 68 million homes.

This map gives an overview of the breadth and scope of the TVA. While on the loop we only touched a piece of the Tennessee River however learned that the TVA is an impressive organization in many ways.

From Grand Rivers we traveled down Kentucky Lake before entering the Tennessee Tombigbee, Tenn Tom Waterway. The Tenn Tom Waterway opened in 1985 to connect the Tennessee and Tombigbee rivers and serves as a link for commercial traffic from the nation’s midsection to the Gulf of Mexico. The benefit of the Tenn Tom is that it provides a shorter and less congested route to the Gulf compared to the Mississippi River, allowing for more cost-effective transportation of goods.

White Cliffs

As we leave the Tenn Tom waterway and enter the Tombigbee River we encounter the white cliffs in Epes, AL. The cliffs are part of the Selma Chalk formation and were deposited at about the same time as England’s famous White Cliffs of Dover. The rivers continue to amaze…

Along the Tombigbee River we anchored at the mouth of the Tensaw River for our last night on the loop.

We had a peaceful anchorage on the Tensaw River and were reminded how much we enjoyed anchoring and wished we had done more of it on our loop journey.

Turning Gold!

Shortly after noon on October 24, 2024 we officially crossed our wake and finished our Great Loop Journey, which started back on May 6, 2023. We entered the harbor in Fair Hope, AL to horns and waves from fellow loopers congratulating us on this momentous occasion.

As I write this log entry almost six months has past and I can still not believe that we completed this amazing journey. Like a lot of “loopers” I could talk about the map below ad nauseam. So many great memories and the good thing is that the not so great memories either are forgotten or seem to convert to valuable lessons learned.

In addition to many memories made on the trip we made a number of friends along the way that we are confident we will stay in touch with for many years to come. In addition to those we met on our loop we continue to meet people around our home port outside of Houston that are planning or dreaming of doing the loop. Meeting with these prospective loopers keeps our loop memories alive.

What’s next for Odysea II is not clear. For now she is under a shed at Houston Yacht Club and we plan to take some short cruises along the Texas coast. We would love to cruise all or part of the Down East Loop however a combination of family commitments and the need to take a break from locks is pushing this cruise out in to the future.

Thank you for following….